OC – For what was the second or third warmest year of all time, it was also a special year for environmental news. In 2019, the world woke up to the climate emergency, young people took to the streets, famous older people were arrested in acts in support for the climate, and governments demonstrated that they could not respond to the appeals of the population.

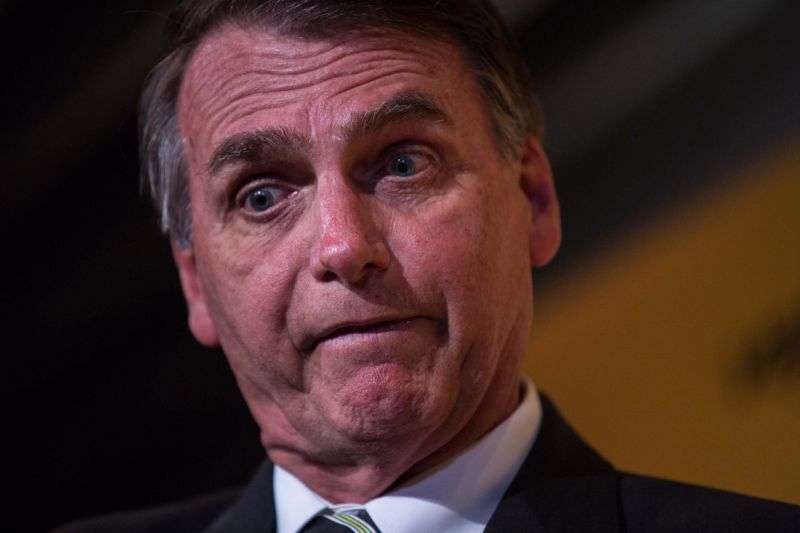

In Brazil, the government of Jair Bolsonaro promoted the environmental agenda as the enemy, paradoxically giving it an unprecedented public visibility. We are experiencing a chronic environmental crisis personified by Ricardo Salles, with poignant episodes: a record number of fires in August, a record oil spill in September, and a deforestation record in November. In January, Brazil had the most fatal environmental disaster in its history, with 270 dead after the rupture of the Vale dam in Córrego do Feijão in Brumadinho. The government is apparently responding to the failure of regulation that allowed this crime with less regulation. In August, the fires in the Amazon Region placed the country at the center of an international crisis, reinforced by the increase in deforestation confirmed in November.

In this retrospective, we have selected some of the events that marked the fight against climate change and fossil fuels during the year.

1 – Greta

In December 2018, a blond adolescent with braids, looking much younger than 15, managed to walk incognito through the corridors of the Katowice climate conference, in Poland. One year later, Greta Thunberg could not repeat her discrete appearances at the COP in Madrid: elevated to the status of a global celebrity, the 16 year old Swedish activist attracted large crowds and cameras wherever she went. Her solitary strikes on Fridays, when she missed school classes to sit in front of the Swedish Parliament demanding more action against the climate crisis, in 2019, transformed Fridays For Future into a global movement. Greta gave furious speeches without sparing adults at the World Economic Forum in February (“I don’t want your hope. I want you to panic”) and at the UN General Assembly in September (“How dare you?”). She has inspired millions of young people to participate in the largest march for the climate in history, on September 20. She has attracted the anger of foolish people, especially the extreme right. And she has become Time magazine’s person of the year for having captured, like no other activist before her, the hypocrisy of the discourse of hope and the chasm between the good intentions declared by governments and their actual actions against greenhouse gases – one day after she was called a “brat” by Jair Bolsonaro.

The youth movement was reinforced by several adult movements. In Europe, the collective Extinction Rebellion promoted acts of civil disobedience that halted London for several days (and ended with many people being arrested). In the USA, celebrities like actress Jane Fonda began protests in front of the Congress in October. Fonda, 81, said her goal was to be arrested once a week. By December 20, she had already been arrested four times during 11 protests.

2 – Deforestation on the rise

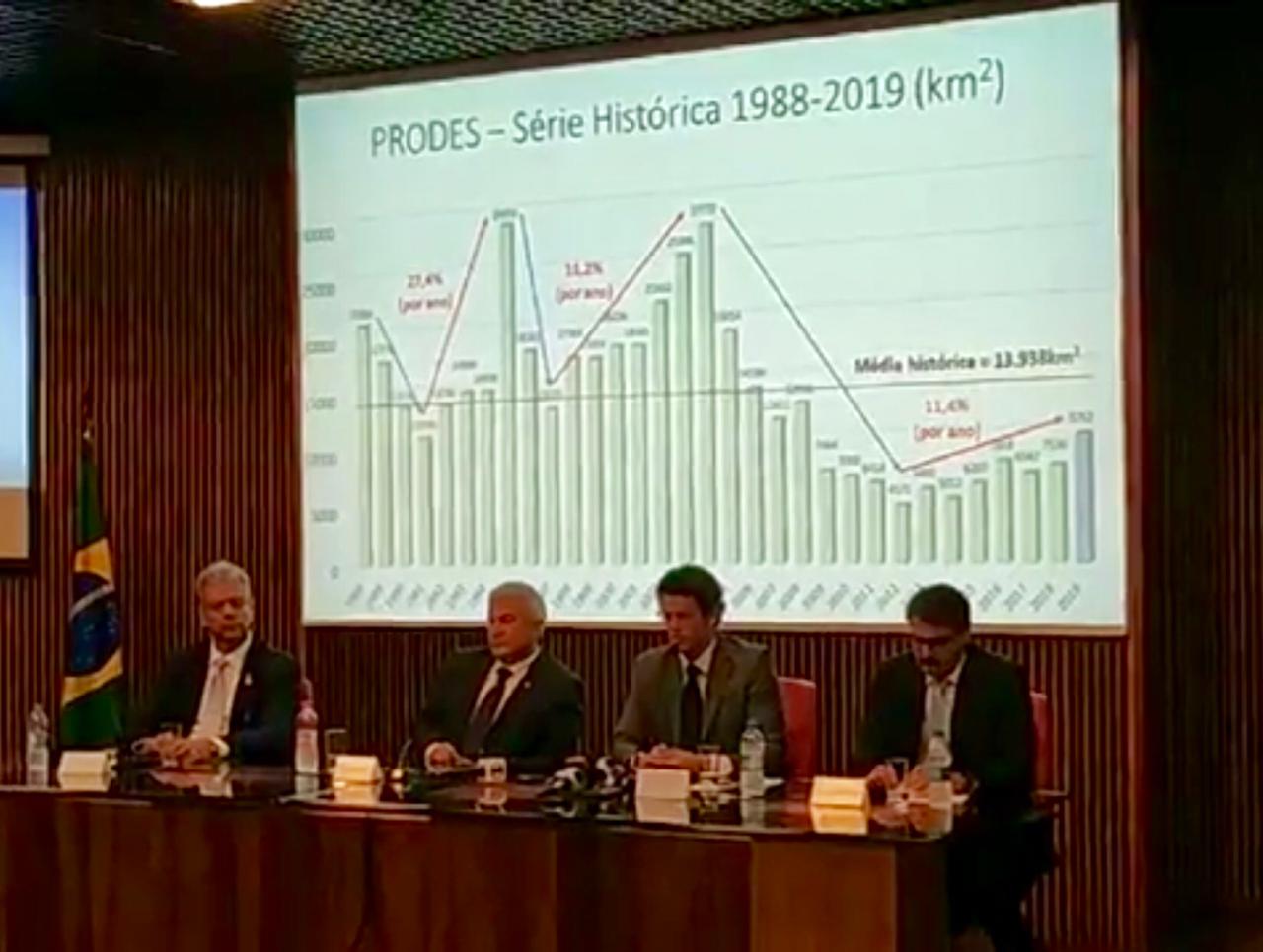

The deforestation rate in the Amazon Region grew 29.5% in the period measured between August 2018 and July 2019. This is the largest deforestation in a decade and the third highest increase in the rate since Inpe began making measurements using the Prodes system, in 1988.

The writing has been on the wall since August of last year, when the presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro promised to end Ibama and the NGOs, by encouraging loggers in the Amazon Region – during the election period, deforestation increased by 50%. After a rainy first quarter, the deforestation began to a show sharp acceleration in May, hitting successive records in June (98% increase in relation the previous July), July (274%) and August (223%). The Deter system, of Inpe, had to twice change the scale of the graphics on its website, in order to accommodate the unprecedented monthly rates. The minister of the Environment called the disclosure of the data as “sensationalism”, and then ordered his trusted aide Evaristo de Miranda to produce a PowerPoint presentation showing the supposed “holes” in the Deter system, which would justify the contracting of a private system in order to “complement” the Inpe information. When the Prodes system showed the loss of 9,762 km2 of forest and confirmed the warnings of the Deter system, the minister then tried to blame rich countries for not giving enough money for conservation.

3 – Brazil as a climate change denier

There was a time when Brazilians could boast about not needing to discuss publicly whether global warming is real or not. We accepted the science and laughed at the Anglo-Saxon world, where the public debate had been hijacked by the fossil fuel lobby, which had delayed the taking of measures against the climate crisis for 20 years.

This changed with the 2018 Brazilian election.

Bolsonaro’s Brazil has joined up with the group of countries in which climate change denial is state policy. Via the office of ideological importation installed in Virginia, we have bought the closed package of obscurantist movements from the USA. The minister of Foreign Affairs professes the ignorant variant of this denial, according to which climate science is a left wing invention to destroy the West and to criminalize the consumption of meat (and heterosexual sex). The minister of the Environment is more aligned with the upfront denial of the 21st century: he admits that climate change exists, but questions whether it is caused by humans. The ministers are not alone: the Brazilian Senate now invites deniers to public hearings and has a denier as the chairman of the joint commission of … Climate Change. Beyond the embarrassment of others, this dissemination of denial signifies that no actual action on climate change will be adopted by this government.

4 – RIP the Amazon Region Fund

What do you do when you have a forest of 4 million square kilometers to preserve and rich countries give you almost R$ 3.5 billion for this? If you are the minister Ricardo Salles, the answer is simple: you give it all up because you don’t like NGOs.

Since February, Salles has been trying to control the Amazon Region Fund, a successful initiative of payments for the reduction of deforestation (REDD+), which has been in force since 2008 in a partnership between BNDES and the governments of Norway and Germany. The objective of the minister was to cut all the funds transferred to civil society and to distribute the money to his agro-business friends. He suggested without any evidence, that NGOs were mismanaging the resources. Or that the fund had no criteria. Or that BNDES, a bank, did not know how to manage money. He tried to rig the management committees of the fund. However, the donors never accepted this. Salles scrapped the committees and since then has been declaring that the return of the fund is “under negotiation.” In reality, the Amazon Region Fund is dead. Governors from the Amazon Region, which together with the Government received most of the funds, are already looking for direct donations.

5 – Galvão does not give in

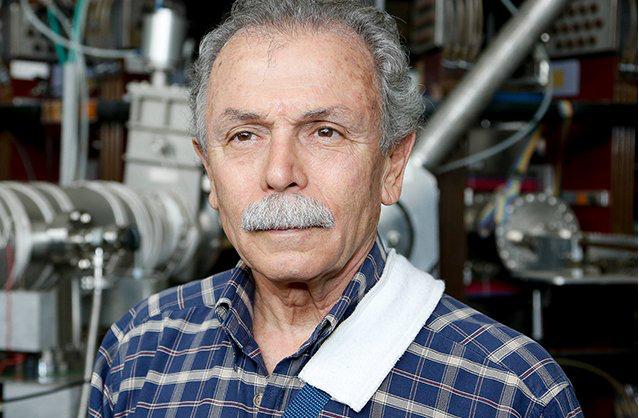

On July 19, before the news of the explosion of deforestation in the Amazon Region in June, Jair Bolsonaro invented a lie to avoid any responsibility. He called the international press to say that the data from the National Institute for Space Research was “lies” and that the director of Inpe, the physicist Ricardo Galvão, 72, should be “working for some NGO.” However, the president did not expect the reaction from Galvão. The next day, Galvão told the newspaper, O Estado de S.Paulo, that the attitude of Bolsonaro was “pusillanimous and cowardly.” The declaration cost him his job, but helped to preserve Inpe, which is an institution that has measured the deforestation in the Amazon Region by satellite for over 30 years. The spotlight of public opinion fell on the institute so that any attempt by the government to manipulate the data would have been immediately perceived. The integrity of the scientist and his decision to confront the government made Galvão a national hero. In December, he was first on the list of the prestigious magazine Nature of the ten people who made a difference in science in the world in 2019.

6 – The effective closure of the Ministry of the Environment

In December 2018, when Ricardo Salles was chosen to be minister of the Environment by Jair Bolsonaro, the Climate Observatory warned that the move sought to extinguish in practice the Ministry of the Environment (MMA) without the burden of closing it down formally. The appointment of a ruralist and, at the time, a defendant (now convicted) in an improbity case, was a result of the desire to subordinate the MMA to the Ministry of Agriculture. We would have liked to have been wrong about this.

However, the first year of Salles management was exactly what was expected: the accelerated dismantling of the ministry was denounced by eight of the nine living ex-ministers. The dismantling began in the actual structure of the ministry when, on the first day of the new government, the department of Climate and Forests (responsible for implementing the commitments of Brazil in the Paris Agreement), the National Water Agency, and the Brazilian Forestry Service ceased to exist. Things got worse with the militarization of the ICMBio, the removal of the heads of IBAMA and the management positions within the ministry itself, the rigging of CONAMA, the restraint on communications and the negligible budgetary execution, even with cash available and many environmental problems to resolve. Up to November 25, the budgetary commitment of the direct administration of the MMA had been less than R$ 3 million, compared to R$ 35.8 million in 2018.

7 – The “knife into IBAMA”

Fined in 2012 for illegal fishing in a conservation area in Angra dos Reis, Jair Bolsonaro spent the first year of his government using the Presidency to promote a vendetta against Ibama, which he called “an industry of fines.” Under the baton of minister Ricardo Salles, and the execution of president Eduardo Bim, the government agency began to persecute the actual inspectors, abandoned intelligence strategies against environmental crime, left most of its superintendencies in the states headless, censored communications with the press – an important element to dissuade environmental crimes –, disclosed locations of operations on the internet, which alerted the criminals, lost funds for strategic areas such as firefighting, and saw the President order the end of the destruction of equipment seized from criminals in protected federal areas. It worked: Ibama applied, in 2019, the lowest number of fines for 15 years, according to published data obtained by the Climate Observatory and published in the report “The Worst is Yet to Come”, launched at COP25. The number of fines for deforestation in the Amazon Region (3,445) was the lowest since 2012, and deforestation was the highest since 2008.

8 – Indigenous peoples become a target

The indigenous lands in the Amazon Region stockpile the equivalent of 42 billion tons of carbon gas and it is therefore fundamental for the global climate balance. They also help to maintain the cycle of rains in Brazil and to conserve the biodiversity – as well as, of course, guaranteeing the survival of over 170 indigenous peoples.

Supported by the military wing, by liberals and by evangelicals, Jair Bolsonaro declared the hunting season open on indigenous lands, which are seen as a restraint to the “development” (which is what they call the exploitation of primary products sold at a bargain price on the international market) and a threat to “sovereignty.” Bolsonaro has promised to open these lands to mining, to agriculture and to timber extraction. The promises have been interpreted as a “free for all.” From January to September, Cimi (the Indigenous Missionary Council) registered 160 invasions of indigenous lands, as opposed to 111 last year. The deforestation in the indigenous lands rose by 65%. Indigenous leaders have been assassinated, such as the guardian of the forest, Paulo Paulino Guajajara, who was killed in an ambush in November in the Arariboia indigenous land, which had been invaded by loggers (two more Guajajaras were killed in early December in the same area). This encouragement for invasions led Bolsonaro to be denounced for genocide by the International Criminal Court.

9 – NGOs become a target

During his campaign, Jair Bolsonaro promised to “end all kind of activism” in Brazil. In his speeches, the president suggested members of NGOs should be sent to places of torture. The minister Ricardo Salles has tried to comply with the presidential promise by financially suffocating the NGOs: first with an official letter (which was illegal and had to be rescinded) determining the suspension of all the agreements of the ministry with third sector organizations; he then froze the Amazon Region Fund. In April, a presidential decree eliminated hundreds of boards with the participation of civil society throughout the Executive, limiting the social control of the federal administration. Next, Conama (the National Council of the Environment) was amended, once again to limit social participation and to increase the control of the government.

The new phase of the elimination of activism seems to be criminalization. At the end of November, four volunteer firefighters were arrested and the office of the Health and Happiness Project was invaded by the Civil Police of Santarém (PA), under the surreal accusation that the environmentalists were behind the fires made by land-grabbers in a protected area in Alter do Chão. In an inexplicable omission of the governor Hélder Barbalho (MDB), the four were indicted during the week of Christmas.

10 – Amazon in flames

On August 10, farmers from the region of Novo Progresso, in Pará, combined by WhatsApp for a “Day of Fire,” a type of collective burning of areas that they had taken over. The fire had the declared objective of “showing service” to President Jair Bolsonaro. It initiated an international crisis. In that month, the number of fires in the Amazon Region was the highest in seven years – triple that registered in the same month in the previous year. It was the largest number of outbreaks of fire recorded in August since the beginning of the fall in deforestation that was not associated with any event of El Niño or extreme drought.

The government reacted first by trying to disqualify the data (they were “campfires,” in the immortal words of the minister). It then tried to relativize it and, finally, when the reality became inescapable, blamed the NGOs and the Indians for the fires. However, all the scientific data showed that the flames were nothing more than the final stage of the forest deforestation, which had accelerated in the second half of the year, as had been shown by Inpe. In September, Bolsonaro reluctantly ordered the Army to help with fighting the fire. The presence of the military, coupled with the return of the rains, meant that the number of fire outbreaks dropped in October. However, the deforestation spiked again in November, as soon as the Army had left. In the dry season, all this taken over forest will burn again.

11 – California in flames

The devastating forest fires in the US state of California have become endemic, just as scientists predicted 30 years ago. In October 2019, Californians watched one more serious fire season, but less severe than 2017 and 2018, which were the worst in history, when more than a hundred people died. This year, the fire season has been accompanied by massive blackouts (something common in large Brazilian cities, but unheard of in the US). The link between the infrastructure of the electricity transmission and the start of the fires has resulted in the energy distributor PG & E declaring bankruptcy, becoming the first bankruptcy related to climate change in the world.

12 – Australia in flames

On the other side of the Pacific, Australia has experienced days of terror since November due to fire, drought and very high temperatures. While this retrospective was being written, the most devastating fires in history were razing the continent, cockatoos falling dead from the trees due to the heat and the Aborigines from the Australian central region being forced to leave their lands – the first Australian climate refugees. In November, hundreds of koalas died in the fires, leading to exaggerated headlines on the species being “functionally extinct.” On December 18, the country had the highest temperature in its history: a national average of 41.9oC, which meant that in some locations the thermometers reached 50°C. The Australian weather service even changed the color code of its temperature maps, using brown to symbolize the hottest regions – due to the lack of darker shades of red. On November 10, Australia recorded, also for the first time in its history, a day without rain in any part of its 7.9 million square kilometers.

The Australian government apparently believes that this is a divine punishment or a “variability of the system.” The Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison – elected in a close race that had the climate crisis as one of its main issues – is a climate denier who wants to maintain the lucrative coal industry. Science has no hesitation in classifying the fires and the heatwave as a direct result of climate change. Maybe Australian voters will listen to science next time.

13 – Fiasco in Madrid

The COP that should not have been took place, and the result only proved that it should not have been. Rejected by Brazil, embraced by Chile, and diverted at the last minute to Spain after the Chilean Spring, COP25 had two missions: to complete the negotiation on carbon markets, closing the so-called “rule book” of the Paris Agreement, and to extract from governments a strong commitment to increase the ambition of their targets to cut emissions (NDCs) for 2020. It failed miserably at both. The so-called article 6 of the agreement (the rules for the markets) was not completed and the exhortation about ambition was generic and, we say, unambitious.

The result was partly the responsibility of the weak presidency of the Chilean minister Carolina Schmidt, but largely the fault of the large emitting countries. One in particular had a particularly detrimental role: Brazil. The minister Ricardo Salles (the same person who had said that COPs were only luxury holidays for civil servants and who had tried to stop the Climate Week, a type of Latin American “mini-COP” in Bahia, claiming it was a mere opportunity for gastronomic tourism) spent two weeks in Madrid heading the Brazilian delegation, which is something previously unheard of, because ministers usually only participate in the last days of negotiation. In between one shopping trip and another, Salles bullied Brazilian diplomats and tried to blackmail other countries to give money to Brazil in exchange for unlocking negotiations. Without precedent, Brazil vetoed mentions of human rights and the climate emergency in the texts under negotiation – and, in the closing plenary, was isolated when trying to remove the mention of oceans in a maneuver in defense of the ruralists. The changes of orientation of Brazil provided a stage to countries like Australia to spoil any negotiation, and the result was a fiasco as not seen since 2009 in a COP. The performance gave Brazil the anti-award of Fossil of the Year, awarded by NGOs to the countries that most hinder the negotiations. In another self-fulfilling prophecy and with his individual decorum, Salles placed the blame on the process and on others for a debacle that he himself had instigated.

14 – Ethanol in a common grave

Trio responsável pela revogação do decreto do zoneamento ambiental da cana-de-açúcar.

Foto: Valter Campanato/Agência Brasil

Does anyone remember ethanol, the biofuel sold by Brazil as sustainable because it did not increase deforestation or compete for land use with food crops? On November 6, the Bolsonaro government acted differently. And justly by the hands of two ministers considered “technical” and “reasonable”: Tereza Cristina (Agriculture) and Paulo Guedes (Economics). In the stroke of the pen, these two and the president and extinguished a prohibition that had been in force for ten years with respect to sugarcane planting in the Amazon Region and in the Pantanal. This time, they had the support of Unica, the sugar-alcohol lobby that one year previously had positioned itself against the end of prohibition (an old desire of some ruralists) by finding that this generated significant image damage for an insignificant economic advantage (which was correct: the designated areas in the country as being suitable for sugarcane are equivalent to six times everything that Brazil has planted of this grass in 500 years, i.e., there is no need to plant in the Amazon Region or in the Pantanal). The decree of November appears to be more a demonstration of the power of the ruralists, who want to eliminate any regulation of their activity. And it provides a signal to other sectors, such as soy and beef that no restriction, whether state or voluntary, is worth more than Brazilian commodities.

15 – Investors react

The anti-environmental policy of Bolsonaro did not go unscathed for two groups of people who are informed by other channels that are not the WhatsApp groups of Carluxo: the investors and international markets. In August, 18 international brands, including Vans, Timberland and The North Face, belonging to the VF Corporation, announced a boycott of Brazilian leather due to the situation in the Amazon Region. In September, it was the turn of H & M, one of the largest retailers in the world. Also in August, groups of investors with US$16 trillion in assets asked the government to take specific measures against the forest fires and demanded that companies explain how they are dealing with the problem. In December, 87 major corporations, including Tesco and Carrefour, wrote to Bolsonaro asking for the maintenance of the moratorium on soya, which has been in force for 13 years, after the producers, meeting in in Aprosoja, promised to overturn it.

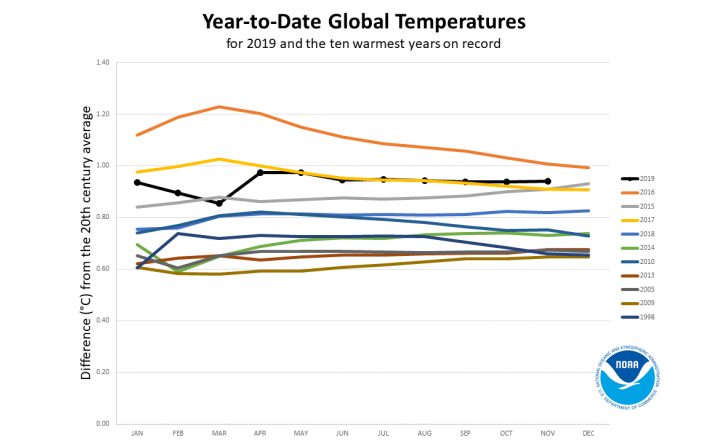

16 – 408, 7.6, 1.1 and 0.6 – the numbers of the year

While the politicians have failed to respond capably to the climate crisis, science has been accounting for the catastrophe in annual reports that show how far humanity is from a safe climate. This year, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) showed that the average temperature of the planet (continents and oceans) will close at 1.1°C, which makes 2019 the second or third warmest year in history. The WMO also disclosed another record of CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere: 407.8 parts per million in 2018, which is 47% above the pre-industrial levels. The IPCC, which this year published two special reports (one on the land and another on the oceans and the cryosphere), showed that, on the continents, global warming has already exceeded the 1.5oC limit recommended by the Paris Agreement. At the end of the year, UNEP (United Nations Environment Program) published a new edition of its Emissions Gap report, according to which humanity needs to cut emissions by 7.6% per year every year from now until 2030 – something that is not even close to being on the horizon – if there is to be a reasonable chance to avoid exceeding the 1.5oC barrier. The “good” news was from the Global Carbon Project consortium: on December 2, it published its annual estimate of global emissions by fossil fuels, showing that in 2019 they “only” increased by 0.6%, which is half the rate recorded in previous year. However, it was meant to fall by 7.6%.

17 – Adieu, Paris

On November 5, surprising nobody, the US president, Donald Trump, sent a letter of withdrawal from the Paris Agreement to the UN, formally initiating the exit process from the treaty. The notification stated that the climate deal was “burdensome” for the United States, but it left open the possibility – seen as infamy by the international community – to return if the Paris Agreement was “renegotiated” under the terms that Trump wants. According to the rules of the agreement, the exit becomes effective one year after the notification. In other words, the US will withdraw on November 4, one day after the presidential election that may remove Trump from power.

Without the United States, the climate of international cooperation seen in 2015 in Paris and fundamental for the success of the implementation of the agreement should not be repeated. Countries in development, for example, have tended to drag their feet with their targets of emission cuts, because the promise of climate financing by the rich countries is more difficult to comply with without the contribution of the richest one of them all. On the other hand, the US emissions are already declining due to technological changes in energy generation – and this will be difficult to reverse, however much Trump likes coal.

18 – #ÓleonoNordeste [Oil in the Northeast]

In 2019, Brazil was longing for the time when the most sinister things mysteriously landing on our beaches were cans of cannabis. In late August, oil stains began to appear in some northeastern beaches, in what would become the largest environmental disaster of the Brazilian coast: 4,500 km of beaches were contaminated, from Rio de Janeiro to Maranhão. In September, large quantities of oil were found on iconic beaches, such as Praia dos Carneiros, in Pernambuco, and Itapoã, in Bahia, as well as in estuaries and mangroves. Despite the declarations of the secretary for Fisheries, Jorge Seif Jr., about the advanced cognition of fish, the northeastern fishing industry suffered a disaster that still cannot be calculated, with the contamination of the fish by the toxic substances in the oil. The government took 41 days to activate the contingency plan against the spills, when the minister of the Environment only discovered that it existed at the end of September. The two committees that had previously managed the quick response had been closed down. The cleaning of the beaches was performed by volunteers, who put their own health at risk, and by local officials from Ibama. To this day, no one knows where the oil came from, or when it will stop arriving on the beaches. The minister Ricardo Salles followed the strategy of his president and blamed Greenpeace for the spill – and received a lawsuit in return. The episode illustrates another risk of the dependence on fossil fuels and indicates how unprepared Brazil is to deal with significant spills in the pre-salt era.

19 – Land-grabbing guaranteed by Jair

On December 11, with COP25 in full swing, Jair Bolsonaro gave a significant Christmas present for the criminals who were involved in the deforestation of the Amazon Region: he issued a Provisional Presidential Decree liberating the regularization of illegally grabbed land until 2018, attending to the whims of his electors who invaded, devastated and occupied public forests in order to speculate with the land, betting on impunity. The Provisional Presidential Decree repeats and amplifies the amnesty to land-grabbing that had been given by Michel Temer and which is the object of an action of unconstitutionality in the Federal Supreme Court.

The occupation of public lands is the main engine of the deforestation in the Amazon Region – and, therefore, the main individual cause of carbon emissions in Brazil: 35% of the deforestation seen in 2019 occurred in unoccupied lands or those without any information about ownership. Different from that claimed by the government, the land-grabbing is performed overwhelmingly by well-organized and well-financed gangs, often led from São Paulo – and not by small, poor farmers. The limit of 2,500 hectares given by the Provisional Presidential Decree of Bolsonaro to make a property capable of regularization also shows that it is the large landowners who will benefit from the presidential measure.